Study Shows Transparent Roundworms Use Chemical Language to Communicate

January 25, 2012

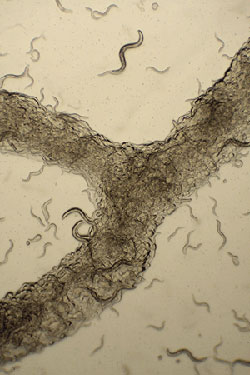

Scientists at the Boyce Thompson Institute and the California Institute of Technology are studying how transparent roundworms communicate. In a new study, they report that these worms, Caenorhabditis elegans, have a highly evolved language in which they combine chemical fragments to create molecular messages that control social behavior. By learning how nematodes communicate, the researchers hope to open new possibilities for nematode prevention and control.

These small, transparent roundworms have a highly evolved language -- they combine chemical fragments to create precise molecular messages that control social behavior, reports a new study co-authored by scientists at the Boyce Thompson Institute.

The research, published in the January issue of PLoS Biology (10:1), holds promise in helping to develop new treatments for the more than 20 percent of the world’s population infected with nematodes and for agricultural producers whose crops are destroyed by the pests.

“Learning about how nematodes communicate opens up new possibilities for prevention of nematode infection in humans and nematode control in agricultural settings,” said co-author Frank Schroeder, a Cornell adjunct assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology and a scientist at BTI, an independent affiliate of Cornell. BTI postdoctoral researcher Stephan von Reuss, one of the two lead authors of the study, added that “using the worms’ own language, we may be able to disrupt their development and reproduction or attract them to lethal environments.”

The worms, Caenorhabditis elegans, is a lab-friendly model species for research on how chemical signals affect development and behavior. In 2008, Schroeder and colleagues had discovered that nematodes use chemical signals as sexual attractants, which provided the first hint that nematodes use chemistry to communicate.

“What we understand now is that nematodes use complex messages that consist of molecules put together in a modular fashion,” said Schroeder. “They put together different chemical fragments depending on what they want to say.”

For example, the researchers found several molecules that tell nematodes to scatter and disperse. These molecules consist of only two building blocks. But adding a third building block called an indole changes the meaning completely: instead of “go away” the message becomes “everybody come here.” Nematode messages get even more complex by combining two or more different molecules, just like combining different words in a sentence makes for more complex meaning.

Schroeder and his team used a new analytical method called comparative metabolomics to analyze the chemicals made by worms. By comparing the body chemistry of normal, wild-type worms with the chemistry of worms that have a signaling defect, i.e., “worms that can’t talk,” the researchers detected molecules that were only present in wild-type worms, but not in “silent” worms. These molecules then turned out to form the “language of the worm.”

These results show that by combining molecules that include different types of chemical building blocks, worms have developed a sophisticated chemical language that they use to organize their communities. The discovery provides a new window into the chemistry of life and suggests that many other animal species including vertebrates may produce similar signaling molecules to control behavior and other biological functions.

As a next step, the researchers will explore how the worms’ nervous system senses and deciphers the different chemical messages. “Understanding the worm’s language is just a first step — we now need to figure out how the worm decodes and makes these molecules,” Schroeder said.

Source: Cornell University

Image: Frank Schroeder, BTI/Cornell

No comments:

Post a Comment