Single Cancer Cells Often Split into Three or More Daughter Cells

July 6, 2012

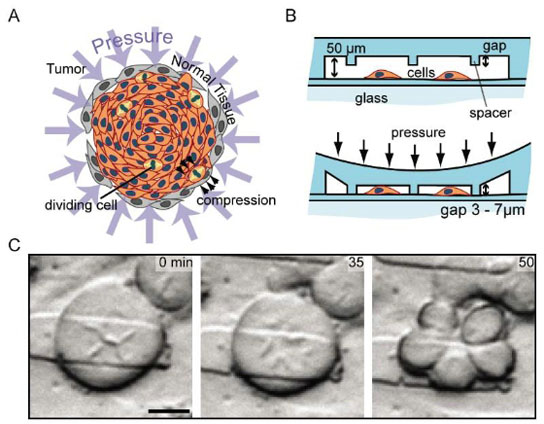

(a) In vivo tumors are subjected to spatially and mechanically challenging conditions

(b) Profile view of microfluidic device

(c) Cell division into five daughter cells

Image credit: UCLA Engineering

(b) Profile view of microfluidic device

(c) Cell division into five daughter cells

Image credit: UCLA Engineering

It’s well known in conventional biology that during the process of mammalian cell division, or mitosis, a mother cell divides equally into two daughter cells. But when it comes to cancer, say UCLA researchers, mother cells may be far more prolific.

Bioengineers at the UCLA Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science developed a platform to mechanically confine cells, simulating the in vivo three-dimensional environments in which they divide, and found that, upon confinement, cancer cells often split into three or more daughter cells.

“We hope that this platform will allow us to better understand how the 3-D mechanical environment may play a role in the progression of a benign tumor into a malignant tumor that kills,” said Dino Di Carlo, an associate professor of bioengineering at UCLA and principal investigator on the research.

The biological process of mitosis is tightly regulated by specific biochemical checkpoints to ensure that each daughter cell receives an equal set of sub-cellular materials, such as chromosomes or organelles, to create new cells properly.

However, when these checkpoints are miscued, the mistakes can have detrimental consequences. One key component is chromosomal count: When a new cell acquires extra chromosomes or loses chromosomes — known as aneuploidy — the regulation of important biological processes can be disrupted, a key characteristic of many invasive cancers. A cell that divides into more than two daughter cells undergoes a complex choreography of chromosomal motion that can result in aneuploidy.

By investigating the contributing factors that lead to mismanagement during the process of chromosome segregation, scientists may better understand the progression of cancer, said the researchers, whose findings were recently published online in the peer-reviewed journal PLoS ONE.

For the study, the UCLA team created a microfluidic platform to mechanically confine cancer cells to study the effects of 3-D microenvironments on mitosis events. The platform allowed for high-resolution, single-cell microscopic observations as the cells grew and divided. This platform, the researchers said, enabled them to better mimic the in vivo conditions of a tumor’s space-constrained growth in 3-D environments — in contrast to traditionally used culture flasks.

Surprisingly, the team observed that such confinement resulted in the abnormal division of a single cancer cell into three or four daughter cells at a much higher rate than typical. And a few times, they observed a single cell splitting into five daughter cells during a single division event, likely leading to aneuploid daughter cells.

“Even though cancer can arise from a set of precise mutations, the majority of malignant tumors possess aneuploid cells, and the reason for this is still an open question,” said Di Carlo, who is also a member of the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA. “Our new microfluidic platform offers a more reliable way for researchers to study how the unique tumor environment may contribute to aneuploidy.”

Other authors on the paper included Henry Tat Kwong Tse and Westbrook McConnell Weaver, both UCLA biomedical engineering graduate students. The research team is currently seeking to partner with cancer researchers to further investigate the importance of confined environments on the development of cancer.

The study was funded by the UCLA Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science.

Source: Matthew Chin and Wileen Wong Kromhout, UCLA Newsroom

Image: UCLA Engineering

No comments:

Post a Comment