Mitochondrial Transfer Technology Could Reduce Risk of Childhood Disease

October 25, 2012

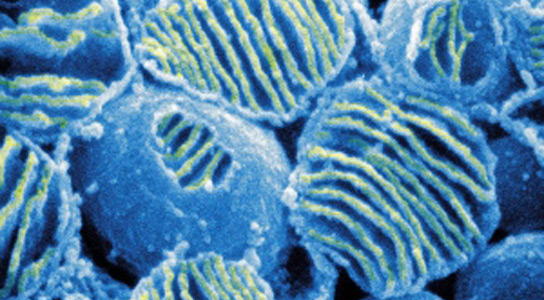

Mitochondria produce energy in cells; swapping them in an unfertilized egg can reduce the risk of disease in the offspring. Image: ISM/SPL

New technology that would allow genetic material to shuffle between unfertilized eggs is ready to make healthier babies. This technique would allow parents to minimize the risk of a range of diseases related to defects in mitochondria.

The scientists published their findings in the journal Nature. Mitochondrial defects affect 1 in every 4,000 children, and can cause rare and fatal illnesses. They are also implicated in a wide range of common diseases, like multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. Mitochondria have their own DNA and are only inherited from mothers. Replacing defective mitochondria in eggs from mothers who have a high risk of passing on such diseases could help spare the children.

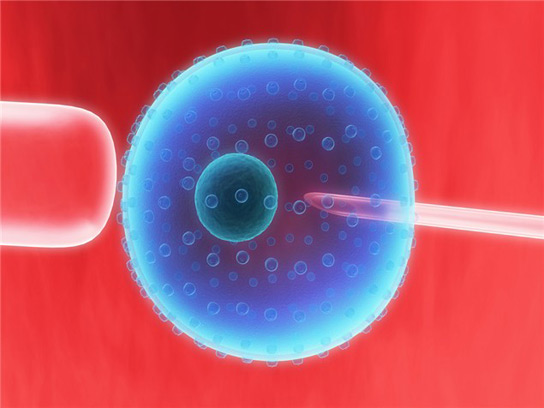

Hybrid embryo containing DNA from one man and two women.

The team reports the creation of human embryos in which all of the mitochondria come from a donor. This method still needs to be tweaked to increase efficiency and gain regulatory clearance, states Shoukhrat Mitalipov. However, this technology will be used in fertility clinics within three years.

Mitalipov initially worked with rhesus monkeys three years ago. The technique the team used is similar for humans. They removed the nucleus from an unfertilized egg, leaving behind all of the cell’s mitochondria, and injected it into another unfertilized egg that had its nucleus removed. Then, the eggs were fertilized in vitro.

In the previous experiment, the team had proven that the fertilized monkey eggs were viable by implanting them into a uterus, where they produced four healthy offspring. In order to evaluate the results with human cells, researchers had to settle for developing the embryos to the blastocyst stage, a ball of about 100 cells. They used these cells to produce embryonic cell lines, and carried out tests on them. The cells looked like normal embryos, but all of the mitochondria stemmed from the donor.

The team also followed up to see if there were any long-term adverse effects from the DNA transfer. None were observed. They also proved that this technique worked with frozen eggs, something that would be crucial in the clinic.

It remains to be seen whether the animals bred in this fashion can successfully have their own offspring, and more data needs to be gathered on the possible abnormalities in both monkey and human embryos.

50% of the human eggs underwent abnormal fertilization, in which excess maternal nuclear DNA remained, a problem seen much less frequently in the monkey tests or in controls. Human oocytes are more sensitive, and that incomplete meiosis caused the problem. The team is trying to tweak the method. Even so, some 20% of the egg produced embryos were suitable for transfer to the uterus.

The US NIH restricts funding for research that destroys human embryos, so Mitalipov used funding from private sources. Clinical work will create eggs that will not be meant to be destroyed, and thus this project might eventually be eligible for public money. The technique must be approved by the FDA, which has authority over reproductive technologies. They submitted an application for approval in January, but so far they have had no response.

Public legislators are wary of creating hybrid babies that have three parents instead of the normal two. This technique does mix the genetic material from a mitochondrial donor. Things might move faster in the UK. A team at Newcastle University has conducted similar experiments, and authorities are considering their stance on this technology.

No comments:

Post a Comment